Paris Journal 2011 – Barbara Joy Cooley Home: barbarajoycooley.com

Photos

and thoughts about Paris

Sign

my guestbook. View

my guestbook. 2010 Paris Journal ← Previous Next

→ ← Go

back to the beginning

|

PLEASE VOTE FOR MY BLOG IN THE GOLDEN BLOG AWARDS! I picked up the free newspaper, Metro, at the shopping mall part of the Saint Germain market. This little French newspaper can be fun, but unfortunately it is not published for much of the summer. Now that it is September, Metro is back, and a place to pick it up is conveniently on my route for daily errands. The fun, big two-page feature in yesterday’s issue is about the anti-fraud program for wine. 419 million cases of wine were produced in France in 2010. This is a smaller production than in the past, but France remains number one in the world in sheer volume of wine production – ahead of Italy and Spain. This represents 9.09 billion euros worth of business. Of that amount, 3.36 billion is for the wines of Bordeaux alone. So many temporary workers were hired to help with the harvest in August that the unemployment rate in France fell by 0.1% that month as a result. This is after three months of increases in the unemployment rate. The responsibility of enforcing quality control and inspecting to assure there is no fraud falls to the customs agents, known as the douaniers. They must 1) control the quality and quantity of production, and 2) collect data about each crop. The data is fed into a massive database called casier viticole informatisé (CVI). This creates an “identity card” for each wine, and provides a useful tool for the justice system to use in determining cases of fraud. An example of a type of fraud that is attempted is over-chaptalisation. Chaptalisation is the practice of adding sugar during production to increase the wine’s alcohol level. Chaptalisation is allowed, but very restricted. Fines for over-chaptalisation are steep. In early 2009, a court in Villefranche-sur-Saône fined 42 producers from 1,000 to 20,000 euros each. To create the “identity cards” for the wines, the douaniers show up with a basket in hand, as they recently did on one fine September morning at the domain of Château Smith Haut Lafitte (which also has its own very interesting anti-fraud device for consumers). Around them, more than a hundred seasonal workers were picking the grapes for this prestigious domain in Bordeaux. The douaniers took 25 to 30 kilos of fresh grapes. After they make it into wine, the wine will be analyzed and the data used to allow for the traceability of the terroir – the area in which those grapes were grown. This work of the douaniers is considered to be essential for guaranteeing security against counterfeiting such a renowned brand. Who would do such a thing, you might ask? Well, according to Metro, Chinese businesses would. Just as businesses in China steal intellectual property and produce knock-off cars, fake designer handbags, cheap electronics, and cheap Eiffel Tower trinkets, they also sell fake Château Lafite Rothschild 1982 (see video about this domain) and the like. These grand crus of the Bordeaux are the principal targets of this illegal activity, attracting buyers from the middle- and upper-classes of China. Romain Vandevoorde, a legitimate importer of wine in Peking, says “There is more of this Lafite 1982 in China than was ever produced in France.” The perps collect used, empty bottles from the bins of restaurants. Hopefully, they wash them, and remove the old labels. They affix new labels which they produce on a computer. Then the bottles are refilled with cheap wine (vin bon marché). In China, some of these bottles can sell for nearly 6,000 euros. One of the douaniers said the proliferation of the counterfeit wine is possible because of the ignorance about wine among the customers. “The day when the consumer can perfectly distinguish a table wine from a grand cru classé, we will have made a great step,” he concluded. Laboratories on a campus at Pessec, near Bordeaux, are the workplace for 50-some people on the team of the chemist Bernard Medina. The team works on tracing fraud in food and beverages – especially wine. According to Bernard, his team’s work is simple: they just verify that what is inside the bottle corresponds to the label on the outside. Each year, more than 3,000 bottles are tested by this lab, at the request of the justice system. It only takes minutes for the team to detect additives, over-chaptalisation, watering-down, or counterfeiting. The lab uses that database I mentioned above, which, for the west of France, has been around since 1992. To build that database, several thousands of kilos of grapes were delivered and turned into wine. “With that, we made a beautiful database,” Bernard says, smiling. “Three weeks ago, our American homologues visited us. They told us they were very envious because when they want to make comparisons, they have to go out to the producers.” Bernard adds, “But then, to taste a Bordeaux, even in a laboratory, it isn’t the worst thing, no?” He’s right! Sign

my guestbook. View

my guestbook. Note: For addresses & phone numbers of some

restaurants in this journal, click

here. |

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

At this

Chinese takeout, the historic painted windows of a former dairy shop are

retained, still advertising the long-gone “fresh eggs of the day.” I adore this practice of retaining beautiful

old commercial façades.

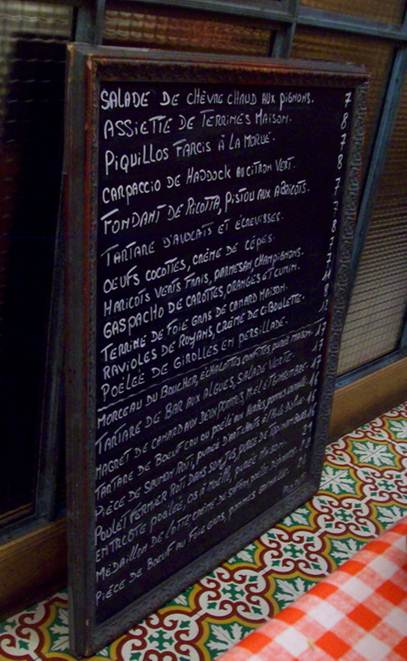

The menu

blackboard at Le P’tit Fernand,

on rue Lobineau by the Saint Germain

market, is moved around from table to table.

A

very fine,

homemade cheese ravioli with chive cream sauce, at Le P’tit

Fernand. We

shared this lovely starter course, which arrived piping hot at the table.

The duck

breast slices cooked a point, and

served in a honey-based sauce with deux pommes:

cooked apples, atop puréed potatoes.

It was excellent, as always; Le P’tit Fernand is a bistro that is reliably good.

Poached

salmon with diced veggies and a purée of artichokes. Delicious! |