Sign

my guestbook. View

my guestbook. ←Previous Next→ Paris Journal 2007 Home

|

Ponies

going home in the evening, up the rue Frémicourt,

East

Asian ceramic tower of some sort in an antiques store

Giant

sundial on the Promenade Plantée, above, and below.

The

Alive! (Vivant!) exhibit on the Seine near the

View of

the tower from the Alive! exhibit.

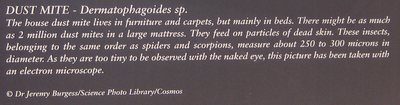

Photo

of dust mite from the Alive! exhibit.

The

Promenade Plantée. |

Thursday, August 23 My good friend Wendy gave me a book, Paris

on a Plate: A Gastronomic Diary, by the witty Australian food critic Stephen Downes. The book is great entertainment. If you like eating and you love Here, at the

beginning of my adventure, I'm taking no chances. Get a few early runs on the gastronomic

scoreboard. You won't believe it, but eating in Chartier is

an easy, relatively short walk from my studio (Monsieur Montebello's studio - and I write that with a envy). I take the rue

Richer, the continuation of the rue des Petites Ecuries, then turn left into

the rue du Faubourg In the nineteenth century, Parisian butchers with business

acumen would brew up a hearty broth from and sell it to customers. Some of

them expanded this sideline, offering simple dishes as well as their

soups. Eventually, some gave away

retailing meat altogether and concentrated on providing cheap, traditional

menus in large dining rooms. These places came to be known as bouillons or ‘boil-ups,’ a synonym for the broth that started it all.

French middle-classes are the world's champions at spotting and following

trends, and bouillons soon became

so popular that they eschewed all modesty and transmogrified into

full-fledged restaurants in grand venues. Never were their origins forgotten,

though, and simple

orthodox French dishes continued to be served. And at cheap

prices. Camille and Edouard Chartier had a chain of bouillons on both sides

of the The place is

packed. Every place at every table in

this gorgeous high-ceilinged space seems taken. I’m led to a table for four – a couple are

just leaving – and seated alongside a husband and wife from Under the

butcher's paper are pink-and-white tablecloths in a tea-towel fabric. The

chairs are well-worn basic timber bistro jobs and the stainless steel cutlery

and glassware are rudimentary (indeed, my knife is more bent than a Kings

Cross cop). Paper napkins are standard, and the floor is in brown linoleum.

Tables butt-join, and you share big baskets of baguettes cut up into generous

slices, salt and pepper, oil, vinegar and mustard with anyone within arm's

reach. Above me is an ancient hat-and-pack rack of three brass tubes. But look

beyond your table for the real joy of Chartier. Bevelled mirrors pattern the walls in a

dazzling check. The massive columns supporting the high ceiling have been

stained chocolate so many times now, it seems, that they appear encrusted.

Chartier is an eating-out relic. A small earthquake might set it to tumbling

down, but Small boxes

on the walls were once for serviettes. They are

numbered, and used to be coveted by Chartier's regulars. At some time in the past, authorities quite

rightly ruled them unhygienic and these days they are empty. The ceiling has

a magnificent skylight surrounded by a border of ornate wrought iron, and the

light here seems remarkably even, if slightly jaundiced. I'm settled

in for less than five minutes before one of Chartier's black-bowtied,

black-waistcoated waiters of a certain age - as many of

them are - seats a woman opposite me.

She is,

I'd

guess,

in her early thirties, has long dark hair and wears a heavy anorak. She

carries a daypack with a koala attached to the zipper. She's

looking all around in awe and wonder, a nice smile of achievement

at having discovered Chartier written all over her face. I smile back

across the table. I notice pink pompoms protruding above the heels of her

sneakers. Her lower calf is ringed with a tattoo of names in a fine cursive

script. The chest of her coarse-knit pullover undulates with a promotion:

'Funnee gril', whatever that might mean. 'Australian?'

I

ask,

because one of your obligations at Chartier is to talk to the others at your

table. 'Nooooo!'

she insists with an immense smile. 'I noticed the

koala,' I say, pointing at the backpack. 'I got it in She's Sioux,

she says, offering her hand across the mustard pot and vinegar and oil

bottles in their perforated sheet-metal holder. From 'You'll like

Chartier,' I say. Yes, she certainly will, she enthuses, but she's

really not used to French food and wants to order something she'll find easy.

She wants only an entrée. You mean a

main-course size? Yes, she says, that's our entrée. It's a starter, I say, in

France and lots of other countries. It's the entry to the meal.

With justification, she looks at me sideways, then scans skywards to take in

Chartier's filigreed iron. We peruse

the list. It's of almost A3 size and chronicles a plethora of offerings under

the rubrics ' poissons '

, 'plats',‘legumes’, 'fromages', 'desserts’ and 'glaces'. And that's not counting

starters (on any given day Chartier has twenty of them). Turn over to find a limited, but cheap,

list of French wines – a bottle of Chartier’s own ‘rouge de table’ costs 4.90 euros. Things like a boiled egg with house-made

mayonnaise costs 2 euros, as do salads of tomato, cucumber, and red

cabbage. You'll pay the same for

grated carrot with a lemon vinaigrette, and a slice of what is known as

Parisian ham - just excellent basic ham for

us - with sour gherkins. Terrine and jellied pork

dishes cost a little more, and I always have the dark maroon,

dense and salty But none of

that helps Sioux. She likes fish, she laughs, because 'Ray?' she

says. 'Is that like a fish with wings?' 'Exactly,' I say. 'In

fact, they call it "wing of ray".' 'Like in

stingray?' she asks. 'It's

wonderful,' I say. 'Not at all what you think.' She looks somewhat

anxious. 'Yes, but

you know, I've snorkeled, and a stingray just surprised me out of nowhere

once, and, oh my God, I nearly died when I saw it.. . So big and all glidey.. . It just kind

of flew past. It was sooo close. I nearly drowned ...' Sioux begins flapping her arms up and down, which

amuses the couple from I explain that

skate is not exactly stingray - probably a

third cousin and much smaller. Sioux draws on her brave Indian progenitors

and orders it. I take the Three slices

of ham with a knob of fresh half-salted butter and plenty of bread are

wonderful. I dive into the breadbasket repeatedly and, when it's

half-empty, a waiter replaces it with freshly cut slices. Sioux goes off amid

the crowds at other tables and snaps away with her digital camera. She is especially taken by the smell and

the look of the old and, like me, has

noticed the gee-gaws of tumbling plaster oak leaves high up on the walls and

the magnificently ornate 'C' for Chartier, which accompanies

them. There's nothing like this in Sioux is an

actress (sometimes), a very good (on her own admission) cocktail mixologist

at other times, and quite a handy waiter. But for the moment she just works and saves to

travel.

It's

her way of getting an education. It will improve her acting. Couldn't agree

more, I say, and I also couldn't help noticing

the names on her calf, even in this cold weather. 'They are my

most important people in the world,' she says, 'and I like to know

they're near.' She pokes out her leg from beneath the table and hoists the

hem of her jeans. A finger traces around the names. 'Charleen is my mom,' she

says, 'and The skate

looks excellent. Pretty plating is no great preoccupation at Chartier, yet

here is a thick piece of wing with capers, chopped chives and small tomato

cubes in what appears to be a

vinaigrette sauce. Three boiled potatoes attend the fish, and they will have

excellent flavour - all French

potatoes do. And there is

a clutch of the world's greatest green salad, mache. My andouillette - grilled chitterling sausage - is accompanied by a formidable pile of chips. 'You know?'

says Sioux, 'I took the 'raie' because of

the capers. I know capers. We sometimes put them in martinis. You know martinis?' Yes, I say, and I love them

made with vodka straight from the freezer. Sioux tends

to her wing delicately, coaxing its soft fibrous texture onto her fork. 'Ray always

looks like the cross-section of some kind of advanced aircraft wing, doesn't

it?' I say. She looks at me strangely. Her face lights up.

It's good, she opines, teasing up another forkful. I try it. Its

flavour is full, and the sauce nicely rounded and lightly oily. Sioux is

looking at my andouillette suspiciously. I've yet to split it open. She wants to

know what kind of sausage it is. I suggest that perhaps she

wouldn't want to know at all. 'Try me,' she declares. Well, it's a sausage

made mainly from the lower bowels of pigs. 'Oh, gross!' she says. 'Now,' I say, 'I'm

going to split it, and you'll see, if you look, a great many curls of bits of

guts and other stuff tumble out onto the plate. And you might smell something

a little . . . "agricultural?" But don't be alarmed. And you don't

have to watch. It's kind of adult-rated food.' I take my

knife to the andouillette. Curls of

gluey skinpale guts spill out, and the characteristic, gorgeous whiff of a

shitty pigpen rises all by itself from the plate. Sioux is mesmerised.

Thunderstruck. Appalled. She pulls a face. She sniffs the air. Tentatively. 'Oh my God!'

she says. 'I can smell it.. . Oh my God! I can! You

can't eat that!' I smile and

shrug and eat, and the andouillette's innards are

sensationally gluey and flavoursome and gelatinous. Sioux is devastated. I can tell by

the despairing look on her face. She sees me as odd, perhaps more beast than

human. Mostly primitive, at any rate. She has stopped eating her skate. She

glances at the andouillette and looks away. She no longer wants to sit opposite me.

Her 'experience' at Chartier has been spoilt forever. And

I'm the culprit. I feel awful. She looks around the room. Two tables away

there is a vacant space next to three young Frenchwomen who are gabbling and

gesticulating, densely involved in office politics, no doubt. 'I'm really

sorry,' says Sioux, picking up her plate of fish and her knife and fork.

'Really sorry. I just can't.. . Just can't..

. That smell is so gross.. . It's the

smell mainly.. . I'm sorry.' And she moves in

alongside the Frenchwomen. Just my

luck, but Chartier is like that. On a good day you can eat well and learn a

little about quantum physics or selling Citroens in Reims, listen to a

diatribe about French taxes or hear Britons boast about the strength of the

pound (they think nobody understands them). But Chartier is always fun, a

living a living treasure. In 1996 it celebrated its hundredth birthday. And

they do something here that was common thirty years ago: the waiters total up

your addition in ballpoint

on the butcher's paper covering your table. I suspect they

take lessons in the ornamental scribble they rip onto the paper. And the

speed at which they compute mentally would dazzle today's teenagers. I keep my bill as a memento before heading

home in this especially damp and cold early winter. |